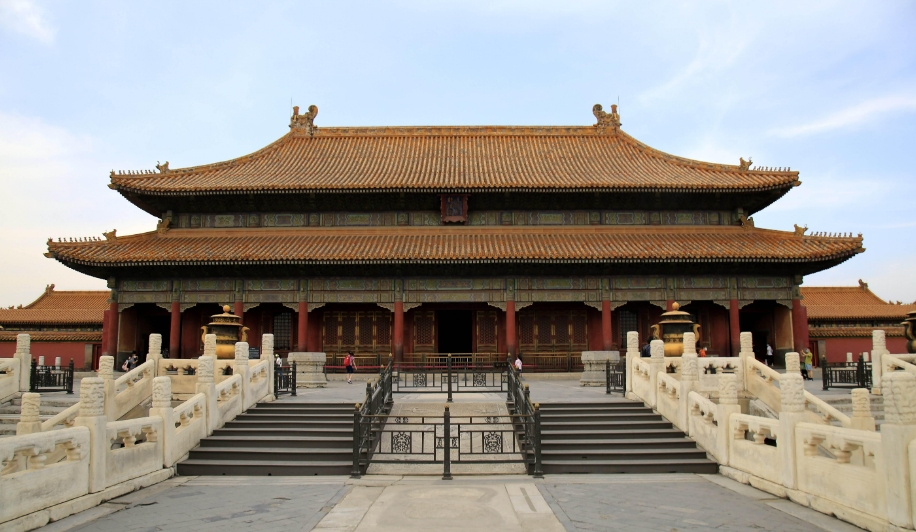

The Forbidden City: A Palace of Power and Tradition

The Forbidden City, nestled in the heart of Beijing, stands as a testament to China's imperial past. More than just a palace, it served as the political and ritual center of the Middle Kingdom for over 500 years. From its completion in 1420 until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the Forbidden City bore witness to the reign of 24 emperors, their families, and a vast network of servants, officials, and concubines.

A City Within a City:

Encompassing over 180 acres and boasting nearly 10,000 rooms, the Forbidden City was truly a city within a city. Surrounded by a 52-meter-wide moat and formidable walls, access was strictly controlled. The very name, "Forbidden City," reflects this exclusivity, derived from the Chinese name "Zijincheng," meaning "Purple Forbidden City." This name referenced the celestial abode of the Purple Star, believed to be the residence of the celestial emperor, further solidifying the earthly emperor's divine mandate to rule.

The Heart of Imperial Power:

The Forbidden City was meticulously designed to reflect the emperor's supreme power and adherence to cosmic order. The complex adheres to a strict north-south axis, with the most important buildings situated along this line. The emperor, considered the Son of Heaven, resided in the northern section, symbolizing his position at the pinnacle of society and his proximity to heaven.

This layout reinforced the Confucian principles of hierarchy and order that permeated every aspect of life within the palace walls. From the grand halls used for state ceremonies and imperial audiences, to the exquisitely decorated living quarters reserved for the imperial family, every space was designed to inspire awe and reinforce the emperor's authority.

A Center of Ritual and Tradition:

The Forbidden City was more than just a seat of power; it was also the stage for a myriad of rituals and ceremonies that maintained social harmony and legitimized imperial rule. Elaborate rituals marked significant events such as the emperor's birthday, the winter solstice, and ancestral worship.

The emperor himself was bound by these rituals, his daily life dictated by a strict timetable overseen by court officials. From the moment he awoke to the time he retired, every aspect of his life, from his clothing to his meals, adhered to established protocol.

Beyond the Walls:

Life within the Forbidden City was a world apart from the bustling capital outside its walls. Thousands of eunuchs and palace women, forbidden from leaving the palace grounds, ensured the smooth functioning of this immense household. They served the imperial family, maintained the buildings and gardens, and upheld the complex systems of etiquette and protocol.

A Legacy Preserved:

Today, the Forbidden City stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, offering a glimpse into the grandeur and intricate workings of China's imperial past. Its magnificent architecture, exquisite artwork, and historical significance continue to captivate millions of visitors each year, making it a poignant reminder of a bygone era.

Q&A

1. What is the significance of the Forbidden City's name?

The name "Forbidden City" reflects the strict access restrictions imposed on the complex. It was derived from "Zijincheng," meaning "Purple Forbidden City," referencing the celestial abode of the Purple Star, symbolizing the emperor's divine right to rule.

2. How did the Forbidden City's layout reflect the emperor's power?

The Forbidden City's north-south axis, with the emperor residing in the northernmost section, symbolized his supreme authority and proximity to heaven. This design reinforced the Confucian principles of hierarchy and order that defined imperial rule.

3. What role did rituals play in the Forbidden City?

Rituals and ceremonies played a crucial role in maintaining social harmony, legitimizing imperial rule, and connecting the earthly realm with the heavens. The emperor's daily life and significant events were governed by strict protocols, reinforcing his position as the Son of Heaven.

note: This return of all, without the author's permission, may not be reproduced