Royal Life in the Imperial Garden

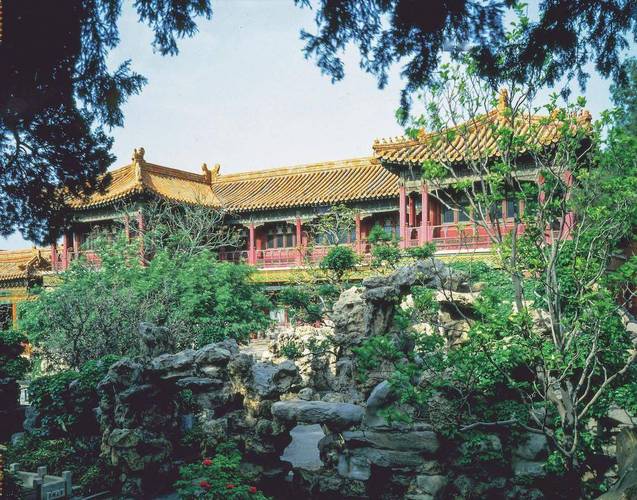

The Imperial Garden of the Forbidden City often graces our screens in historical dramas, depicting a vast and beautiful landscape where concubines leisurely stroll, engaging in subtle power struggles amidst the flora. However, a visit to the actual garden might surprise you with its relatively modest size.

The Reality of the Imperial Garden

Covering a mere 1.2 hectares (18 mu), the Imperial Garden is indeed smaller than one might imagine. This discrepancy between perception and reality doesn't diminish the garden's significance. Established in 1420 during the Ming Dynasty, it was initially known as the "Rear Garden" before being renamed "Imperial Garden" during the Qing Dynasty. Situated on the central axis of the Forbidden City, just north of the Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kuning Gong), the garden holds historical and symbolic weight.

Exploring the Garden's Features

The Gate of Heavenly Harmony (Tianyi Men), built in 1535, stands as a prominent feature. Originally named "Gate of Heavenly Unity" during the Ming Dynasty, it was renamed during the Qing Dynasty. The name "Tianyi" draws from the Book of Changes, specifically the line "Heaven creates water," symbolizing auspiciousness and aligning with the north's association with the water element in traditional Chinese cosmology.

Guarding the gate are two mythical creatures known as Xiezhi. With their piercing gazes and single horns, these symbols of justice and wisdom add a mythical aura to the entrance. A towering bronze incense burner, dwarfing human height, emphasizes the grandeur associated with even everyday objects in the imperial court.

Ancient Trees and Symbolic Plants

South of the incense burner, a pair of intertwined cypresses, estimated to be between 100 and 300 years old, captivates with their intertwined branches, representing unity and longevity. Throughout the garden, ancient trees, with their sturdy trunks and branches reaching for the sky, stand as silent witnesses to centuries of history.

In the southeastern part of the garden, a Chinese scholar tree (Sophora japonica), with its twisting branches resembling a dragon in motion, adds a touch of dynamism. Numerous pines and cypresses provide ample shade during the summer months, offering respite from the scorching sun.

Near the north gate's shadow wall, nestled between two cypresses, a bronze elephant kneels, its trunk touching the ground, symbolizing peace and prosperity.

Seasonal Beauty

The Imperial Garden offers a spectacle of colors throughout the year. Spring welcomes visitors with delicate apricot blossoms adorning the Jade Green Pavilion (Yucui Ting). As spring transitions to summer, vibrant peonies steal the show. Their reds appear even more striking against the backdrop of crimson walls, while white peonies radiate a delicate beauty.

Summer transforms the garden's lake into a mesmerizing display of lotus flowers, their elegant blooms rising above the water's surface. The southeast corner houses the Crimson Snow Pavilion (Jiangxue Xuan). Legend has it that during the Qianlong Emperor's reign, the pavilion was adorned with crabapple trees, their fallen petals resembling a blanket of crimson snow, hence its name. However, during the Daoguang era, the crabapple trees were replaced with crepe myrtles, whose white petals, while beautiful, fail to evoke the image of crimson snow.

Imperial Leisure and Celebrations

Every detail within the garden speaks of imperial refinement. Exquisitely carved stone tables and benches, adorned with intricate dragon and phoenix motifs, provided resting spots for the emperor, empress, and concubines. The garden's pavilions, equipped with doors and windows, offered shelter from the elements, allowing for year-round enjoyment of the scenery.

The Pile of Beauty Hill (Duixiu Shan), constructed from towering Taihu rocks near the garden's exit, is crowned by the Imperial View Pavilion (Yujing Ting). From this vantage point, the emperor and empress would overlook the surroundings during festivals like the Double Ninth Festival. The garden served as a backdrop for numerous imperial celebrations, including the Dragon Boat Festival, Mid-Autumn Festival, and Double Seventh Festival, where the emperor and empress would often host gatherings for the court.

Beyond the Walls

Exiting the Imperial Garden, one encounters the Meridian Gate (Shenwu Men), the Forbidden City's southern entrance. While some visitors might find the garden's scale underwhelming compared to grander gardens in southern China, it's essential to remember that the lives of the emperors, empresses, and concubines extended far beyond the confines of palace intrigue often portrayed in dramas.

Especially during eras blessed with wise rulers, their focus extended to the well-being of their subjects and the prosperity of the nation. The Imperial Garden, while offering a glimpse into the leisurely aspects of royal life, represents only a fragment of the complex tapestry that was life within the Forbidden City.

Q&A

Q: What is the significance of the name "Tianyi Men"?

A: The name "Tianyi Men," meaning "Gate of Heavenly Harmony," is derived from the Book of Changes and symbolizes auspiciousness. It reflects the belief that heaven creates water, aligning with the north's association with the water element in Chinese cosmology.

Q: How did the Crimson Snow Pavilion get its name?

A: Legend has it that during the Qianlong Emperor's reign, the pavilion was adorned with crabapple trees. When these trees were in bloom, their fallen petals resembled a blanket of crimson snow, hence the name "Crimson Snow Pavilion."

Q: What purpose did the Imperial Garden serve beyond leisurely walks?

A: The Imperial Garden was not just a place for relaxation; it also served as a venue for imperial celebrations and festivals. The emperor and empress would often host gatherings and ceremonies within the garden, making it an integral part of court life.