The Forbidden City: A Microcosm of Ancient Chinese Order

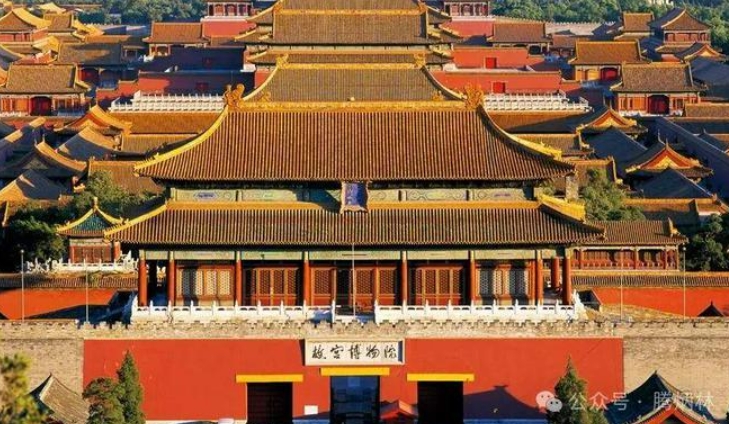

Nestled in the heart of Beijing, the Forbidden City, also known as the Palace Museum, stands as a testament to China's imperial past and a masterpiece of ancient architecture. More than just a palace, it represents a microcosm of the Chinese cosmos, meticulously designed according to philosophical and cosmological principles.

The Forbidden City's layout draws heavily from the "Kaogongji" chapter of the "Rites of Zhou", an ancient Chinese text outlining urban planning principles. This text advocates for a specific configuration: "On the left are the ancestral temples, on the right are the altars of the gods of land and grain, facing the court, and markets at the rear." This ideal layout, emphasizing balance and hierarchy, is embodied in the Forbidden City's structure.

The Forbidden City sits squarely on Beijing's north-south axis, stretching for eight kilometers and forming the city's spine. This central positioning reinforces the emperor's position as the link between Heaven and Earth, the axis mundi around which the world revolved. The palace complex itself is laid out with meticulous symmetry, with the buildings and courtyards mirroring each other along a central axis running from south to north.

Beyond the walls of the Forbidden City, the principles of the "Kaogongji" are also evident. To the left, or east, where the ancestral temples should stand, lies the Working People's Cultural Palace, which during the Ming and Qing dynasties housed the Imperial Ancestral Temple (Taimiao). Here, emperors performed rituals to venerate their forefathers, acknowledging the significance of lineage and ancestral worship in Chinese culture.

On the right, or west, mirroring the altars of the gods of land and grain, lies Zhongshan Park. This park occupies the site of the former Altar of Land and Grain (Shejitan), where emperors conducted rituals to ensure bountiful harvests and appease the forces of nature. The presence of these religious sites flanking the palace highlights the emperor's role not only as a political leader but also as the intermediary between the heavens and his people.

Further reinforcing the "Kaogongji" layout, the area in front of the Forbidden City, once home to government offices, housed the bureaucratic machinery of the empire. Here, officials diligently carried out the emperor's decrees, representing the "court" aspect of the prescribed layout.

Finally, behind the Forbidden City, bustling markets thrived, fulfilling the "markets at the rear" element of the ideal city. This bustling commercial activity, although physically separated from the palace, remained under the watchful eyes of the imperial court, representing the interconnectedness of all aspects of life under the emperor's rule.

The Forbidden City, therefore, transcends its physical form. It is a tangible representation of ancient Chinese beliefs, a microcosm of their universe, and a testament to the power of architectural design to embody philosophical and cosmological principles.

Q&A:

1. What ancient Chinese text influenced the layout of the Forbidden City?

The "Kaogongji" chapter of the "Rites of Zhou," an ancient text outlining urban planning principles, heavily influenced the Forbidden City's layout.

2. What is the significance of the Forbidden City's location on Beijing's north-south axis?

The central positioning reinforces the emperor's position as the link between Heaven and Earth, emphasizing his role as the axis mundi around which the world revolved.

3. How does the presence of the Imperial Ancestral Temple and the Altar of Land and Grain reflect the principles outlined in the "Kaogongji"?

These religious sites, located on the east and west sides of the Forbidden City respectively, correspond to the "ancestral temples on the left" and "altars of the gods of land and grain on the right" as described in the "Kaogongji," emphasizing the emperor's role as both a political and spiritual leader.