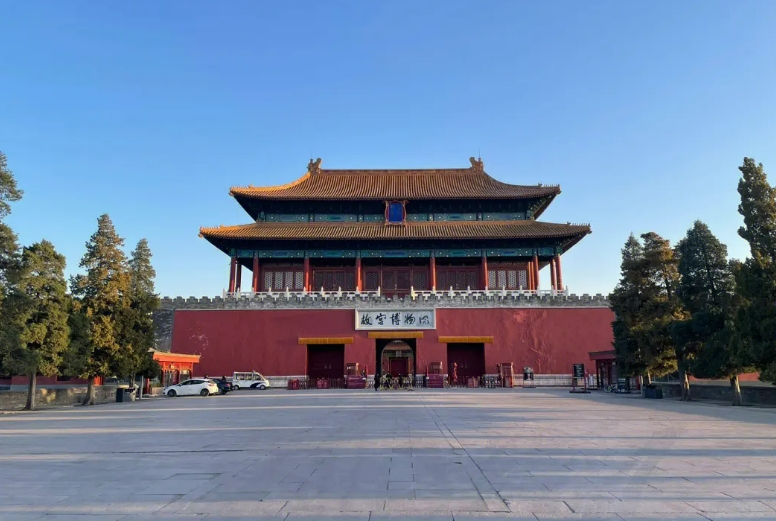

A Monument to Imperial Might: The 14-Year Construction of the Forbidden City

The Forbidden City, a sprawling complex of gilded halls and crimson walls, stands as a testament to the power and artistry of the Ming Dynasty. Its construction, a monumental undertaking, spanned fourteen years, from 1406 to 1420, demanding the skill of 100,000 artisans and the labor of up to a million workers. This vast workforce, drawn from every corner of the empire, dedicated themselves to realizing the grand vision of the Yongle Emperor, who sought to create a palace unrivaled in its splendor and scale.

The construction itself unfolded like a meticulously orchestrated symphony of human effort. The first stage involved transporting immense quantities of raw materials, a logistical feat of astonishing complexity. Millions of bricks, fired in kilns outside Beijing, were transported alongside enormous blocks of marble quarried from quarries near Beijing. The most prized material, however, was the fragrant Phoebe zhennan wood, known for its durability and resistance to decay. These massive logs, some weighing over 20 tons, were sourced from the remote jungles of southwestern China and transported over treacherous mountains and rivers, a journey that could take years to complete.

Once the materials arrived, skilled artisans, master carvers, and masons, set about shaping the Forbidden City into existence. They carved intricate dragons and phoenixes into the marble, their chisels bringing auspicious creatures to life. They sculpted roof ridges with mythical beasts, warding off evil spirits and fire, and fitted together millions of glazed roof tiles, each meticulously placed to create the iconic yellow roofs that symbolize imperial authority.

The most important halls, where emperors held court and conducted affairs of state, demanded materials and craftsmanship of the highest order. Their massive pillars, intended to showcase imperial strength and longevity, were hewn from single, enormous trunks of the precious Phoebe zhennan wood. These pillars, some soaring over forty feet, were meticulously chosen for their straight grain and flawless beauty, their surfaces polished to a gleaming sheen that reflected the intricate ceiling paintings above.

The Forbidden City, born from this monumental effort, stands today as a UNESCO World Heritage site, a testament to the organizational genius and artistic brilliance of its creators. Each intricately carved detail, each precisely placed tile, whispers tales of the fourteen years of sweat, skill, and sheer human determination that brought this iconic palace to life.

Q&A

1. What kind of wood was used for the pillars in the most important halls of the Forbidden City?

The pillars in the most important halls of the Forbidden City were crafted from Phoebe zhennan wood, also known as Chinese nanmu. This wood, prized for its durability, fragrance, and resistance to decay, was sourced from the jungles of southwestern China.

2. How many people were involved in the construction of the Forbidden City?

The construction of the Forbidden City involved a staggering workforce. It is estimated that 100,000 skilled artisans, including carpenters, masons, and carvers, contributed their skills to the project. Additionally, up to a million laborers were employed in tasks requiring immense physical strength, such as transporting materials and preparing the site.

3. Why did the construction of the Forbidden City require materials from distant locations?

The Forbidden City's construction demanded materials that were not readily available near Beijing. The massive logs of Phoebe zhennan wood, essential for the pillars in the main halls, had to be transported from the remote jungles of southwestern China. Similarly, the high-quality marble used for numerous architectural elements was quarried from sites located considerable distances from the capital. This sourcing of materials from across the empire highlighted both the vastness of Ming Dynasty territory and the emperor's ability to command resources on a grand scale.