Forbidden City: Was it Truly Forbidden?

The Forbidden City, nestled in the heart of Beijing, stands as a majestic testament to China's imperial past. Its sprawling courtyards, resplendent palaces, and intricate gardens weave a tapestry of power, artistry, and mystery. The very name evokes an aura of impenetrability, hinting at a place shrouded in secrecy and off-limits to ordinary mortals. But how accurate is this perception? Was the Forbidden City truly "forbidden," or is there more to the story than meets the eye?

The term "Forbidden City" is a translation of the Chinese name 紫禁城 (Zǐjìnchéng), which literally translates to "Purple Forbidden City." The "Purple" refers to the North Star, Polaris, considered the celestial emperor's residence in ancient Chinese astronomy. Associating the emperor's earthly abode with the celestial realm underscored his divine mandate to rule. The "Forbidden" aspect stemmed from the strict regulations surrounding access.

These structures were designed in strict accordance to the traditional code of architectural hierarchy, which designated specific features to reflect the paramount authority and status of the emperor. For example, the emperor's throne room, the Hall of Supreme Harmony, is the largest structure in the Forbidden City, situated on a three-tiered marble terrace, emphasizing his position as the Son of Heaven. Similarly, the use of yellow roof tiles, a color exclusively reserved for the emperor, further reinforced the visual language of power.

Ordinary mortals were forbidden—and most would never dare—to come within close proximity to this imperial city. Access was strictly regulated, reserved primarily for the imperial family, courtiers, concubines, eunuchs, and those with special permission. Commoners were generally prohibited from entering, with trespassing often carrying severe punishments, even death.

However, to claim the Forbidden City was entirely inaccessible to the public would be an oversimplification. There were exceptions to the rule. During festivals like Chinese New Year, the emperor would grant temporary access to a limited number of commoners, allowing them a glimpse into the otherwise restricted domain. These occasions were met with great excitement and were seen as a rare honor by those fortunate enough to participate.

Moreover, the Forbidden City was not an entirely closed system. It functioned as a microcosm of the empire, requiring a significant workforce to maintain its operations. Artisans, craftsmen, laborers, and servants all played crucial roles in the day-to-day functioning of the palace complex, though their movements and interactions were carefully monitored and controlled.

Therefore, the notion of the Forbidden City as entirely "forbidden" requires nuance. While it's true that access was strictly limited and heavily guarded, serving primarily as the emperor's residence and the seat of imperial power, it wasn't completely impenetrable. The controlled access served to reinforce the emperor's authority and maintain an aura of mystique, further solidifying his position as the supreme ruler.

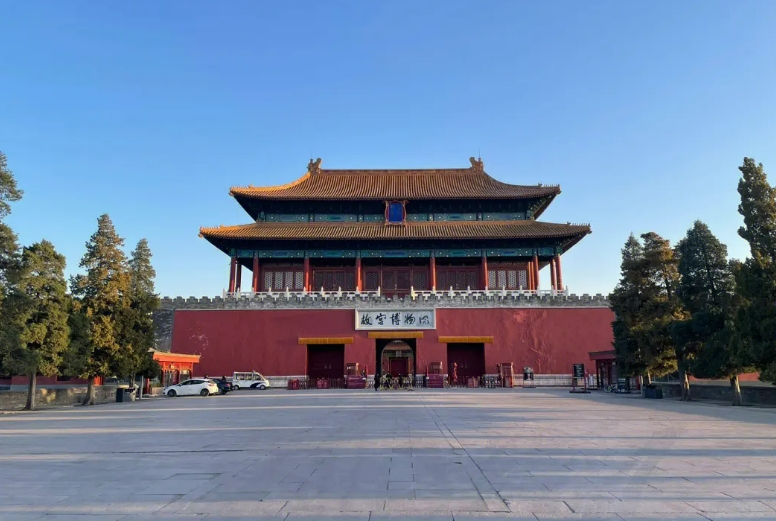

Today, the Forbidden City stands as a UNESCO World Heritage site, its gates open to visitors from around the world. It serves as a poignant reminder of China's imperial past, offering a glimpse into a world governed by strict hierarchies and ancient traditions. While its days as a truly "forbidden" city are long gone, its legacy continues to captivate and intrigue, urging us to delve deeper into the complexities of its history.

Q&A

1. What is the literal translation of "Forbidden City" in Chinese?

A: The literal translation of "Forbidden City" in Chinese is 紫禁城 (Zǐjìnchéng), which means "Purple Forbidden City."

2. How did the architectural design of the Forbidden City reflect the emperor's power?

A: The architectural hierarchy of the Forbidden City, with its emphasis on size, placement, and specific design elements like yellow roof tiles, directly reflected the emperor's supreme authority and status as the Son of Heaven.

3. Were there any occasions when ordinary people were allowed to enter the Forbidden City?

A: Yes, there were limited occasions, primarily during festivals like Chinese New Year, when the emperor granted temporary access to a small number of commoners. This was considered a great honor and a rare glimpse into the otherwise restricted imperial city.