The Forbidden City: A Seat of Power and Protection

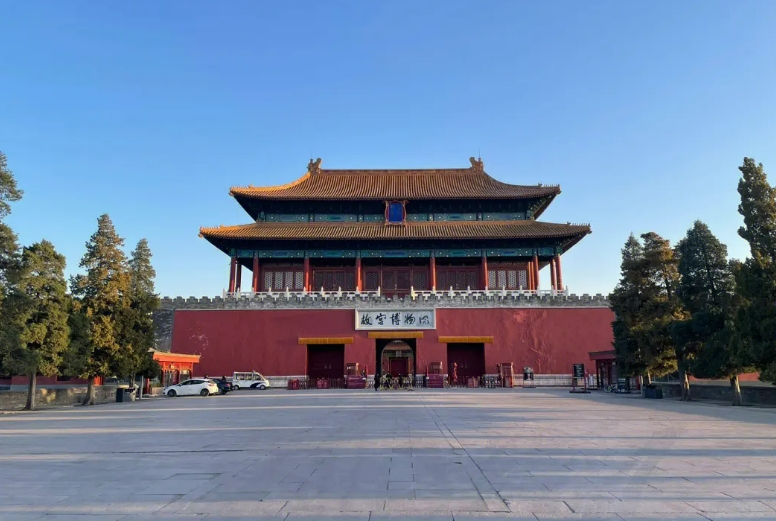

The Forbidden City, a sprawling complex of palaces, courtyards, and gardens nestled in the heart of Beijing, stands as a testament to the ambition and power of the Ming dynasty. Its construction, initiated in 1406 on the orders of Zhu Di, the Yongle Emperor, was not merely about creating a beautiful residence. The Forbidden City was envisioned as a potent symbol of imperial authority and a fortress designed to ensure the security of the emperor and his court.

Consolidating Imperial Power:

- A Capital Fit for an Emperor: Zhu Di, having usurped the throne from his nephew, sought to legitimize his rule. Moving the capital from Nanjing to Beijing, his power base, was a strategic maneuver. The construction of the Forbidden City in this new capital served to further cement his claim as the rightful emperor.

- Architectural Grandeur and Symbolic Language: The sheer scale and magnificence of the Forbidden City, with its 980 buildings and nearly 10,000 rooms, was meant to awe and intimidate. Every element, from the imposing gates and towering walls to the color schemes and mythical creatures adorning the roofs, was imbued with symbolism reinforcing the emperor's divine right to rule. The layout itself, strictly hierarchical with the emperor's residence at its core, visually represented the emperor's position at the pinnacle of power.

- Display of Wealth and Resources: The construction of the Forbidden City was a massive undertaking, requiring the labor of millions and vast quantities of precious materials sourced from all corners of the empire. This not only showcased the emperor's wealth and the empire's prosperity but also served as a stark reminder of his absolute control over the nation's resources and manpower.

Ensuring the Emperor's Security:

- An Impregnable Fortress: The Forbidden City was designed as much for defense as for grandeur. Its high, thick walls, surrounded by a wide moat, created a formidable barrier against potential attackers. Strategic placement of gates, watchtowers, and hidden passages further enhanced its defensive capabilities.

- Isolation and Control: The very name "Forbidden City" highlights its function as a restricted zone. Access was tightly controlled, with only the emperor, his family, his concubines, and a select few officials and servants permitted to enter. This isolation protected the emperor from potential threats both from within the court and outside forces.

- A Symbol of Order and Control: The Forbidden City, with its strict protocols and intricate rituals, reflected the emperor's desire for order and control. This extended beyond physical security to encompass the very functioning of the empire, with the Forbidden City serving as the nerve center from which the emperor and his officials governed the vast Ming dynasty.

The Forbidden City, therefore, was much more than a palace. It was a physical manifestation of imperial power, a carefully crafted stage upon which the Ming emperors played out their roles as Sons of Heaven, and a fortress designed to keep them secure at the heart of their empire.

Q&A

1. What was the main reason for moving the capital to Beijing?

Zhu Di, the Yongle Emperor, moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing primarily to consolidate his power. Beijing was his power base, and relocating the capital there allowed him to better control the government and the military.

2. How did the architecture of the Forbidden City reflect the emperor’s power?

The Forbidden City's architecture was designed to inspire awe and communicate the emperor's absolute authority. Its grandeur, symbolism, and hierarchical layout all reinforced the idea of the emperor's divine right to rule and his central position within the cosmos.

3. What were some of the security measures incorporated into the Forbidden City’s design?

The Forbidden City was designed as a fortress, featuring high walls, a wide moat, strategic gates, and watchtowers. Strict access control and a complex system of inner courtyards and passages further enhanced the emperor's security.

note: This return of all, without the author's permission, may not be reproduced