The Forbidden City: A Palace Fit for the Son of Heaven

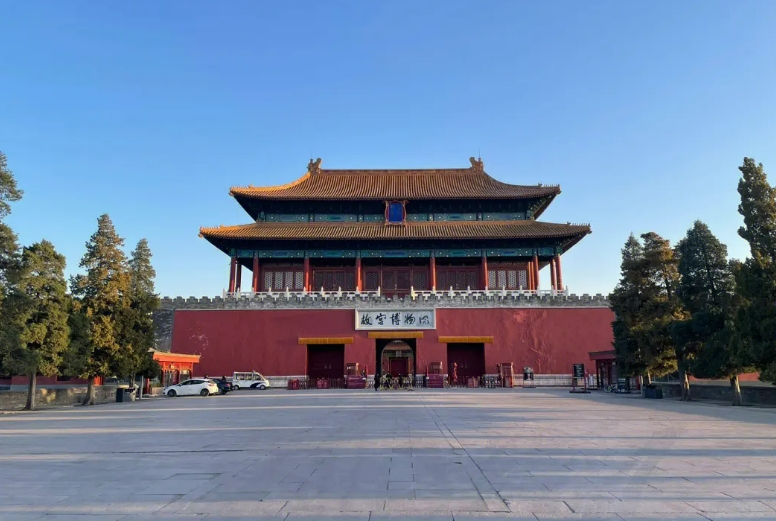

Nestled in the heart of Beijing, a sprawling complex of crimson walls and golden roofs beckons with an air of imperial grandeur. This is the Forbidden City, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a testament to the architectural prowess and cultural legacy of China. But why is this magnificent structure referred to as both the Forbidden City and the Palace Museum?

The answer lies in understanding the site's dual identity: a former imperial palace and a modern-day museum. While today it serves as a captivating museum showcasing China's rich history and art, it was once known as the Forbidden City - a name that speaks volumes about its past.

The Purple Forbidden City: A Celestial Abode

So why was it called the Forbidden City? The answer lies in the ancient Chinese belief system, which placed great importance on celestial alignments and symbolism. The name “Forbidden City” in Chinese is "紫禁城" (Zǐjìnchéng), which literally translates to "Purple Forbidden City." The "purple" in this context refers to the North Star, also known as the Purple Star or Ziwei Star.

In traditional Chinese astronomy, the North Star held a position of supreme importance. It was considered the celestial emperor, residing in the center of the heavens, much like the emperor ruled from the heart of the earthly realm. The Forbidden City, built to house the emperor and his court, was therefore envisioned as a mirror image of this celestial order. The emperor, considered the "Son of Heaven," resided in the palace located directly beneath the North Star, thus symbolizing his central position in both the earthly and celestial hierarchies.

The term "forbidden" further emphasizes the sacred and inviolable nature of the palace. Access to the Forbidden City was strictly regulated, reserved solely for the emperor, his family, his concubines, and those who served him directly. Commoners were forbidden from entering, and unauthorized entry was punishable by death. This exclusivity further reinforced the emperor's absolute authority and the divine mandate he was believed to possess.

Architectural Splendor: A Symphony of Colors and Symbolism

The architectural design of the Forbidden City further reinforces this celestial symbolism. Constructed between 1406 and 1420, the Forbidden City is a masterpiece of traditional Chinese architecture. Its 980 buildings, with their distinctive yellow glazed tile roofs, represent the supremacy of the emperor, as yellow was the color associated with imperial power.

Beyond the color yellow, the palace is a symphony of colors, each imbued with symbolic meaning. The dominant use of red on the walls and pillars represents happiness, good fortune, and prosperity. The white marble bases of the buildings symbolize purity and stability. Green, the color of nature and growth, is featured in the glazed tiles adorning the roofs of lesser buildings.

The Forbidden City, with its celestial name, architectural grandeur, and rich symbolism, stands as a potent symbol of China’s imperial past. Today, as the Palace Museum, it offers a captivating glimpse into a bygone era, inviting visitors to walk in the footsteps of emperors and experience the splendor of one of the world’s most iconic architectural marvels.

Q&A

Q: When did the Forbidden City cease to be the residence of the emperor?

A: The last dynasty to rule from the Forbidden City was the Qing dynasty. In 1912, with the abdication of the last emperor, Puyi, the Forbidden City ceased to be the imperial residence.

Q: How many buildings are there in the Forbidden City?

A: The Forbidden City is a sprawling complex comprising 980 buildings, each intricately designed and constructed.

Q: What is the significance of the color yellow in the Forbidden City?

A: Yellow holds immense significance in Chinese culture, symbolizing the earth and representing imperial power. The use of yellow glazed tiles on the roofs of most buildings in the Forbidden City signifies the emperor's supreme authority and his connection to the heavens.

note: This return of all, without the author's permission, may not be reproduced