Why Were Concubines and Workers Buried Alive with the Emperor?

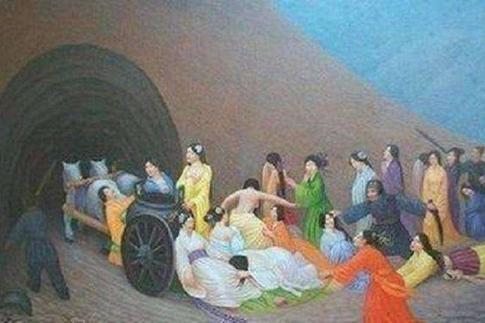

The practice of burying concubines and workers alive with a deceased emperor was a horrifying ritual primarily practiced in ancient China. This inhumane act stemmed from a complex web of beliefs and societal structures, leaving behind a chilling legacy.

Ensuring the Emperor's Afterlife

In ancient Chinese cosmology, death was not an end but a transition to the afterlife. The emperor, considered the Son of Heaven, was believed to require the same comforts and retinue in death as he enjoyed in life.

- Maintaining Status in the Afterlife: Concubines, servants, and even skilled artisans were seen as essential possessions, ensuring the emperor maintained his status and lifestyle in the afterlife. This practice reflected the belief that social hierarchies extended beyond the mortal realm.

- Serving the Emperor's Spirit: The buried individuals were expected to continue their duties, providing companionship, entertainment, and services to the emperor's spirit.

- Preventing "Uncleanliness": Some sources suggest a fear of leaving concubines "unclean" – widowed and without a clear societal role. Their deaths were seen, disturbingly, as a way to preserve order and prevent potential instability caused by their independent existence.

The Terracotta Army: A Substitute for Human Sacrifice?

The most famous example of this practice is the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China. While his tomb remains unexcavated, historical records describe the burial of numerous concubines and workers alongside him. However, his tomb is also guarded by the famed Terracotta Army, thousands of life-sized clay soldiers.

- Evolving Practices: The Terracotta Army might represent a shift away from human sacrifice. It's possible that as sensibilities changed, these figures served as symbolic replacements for living individuals.

- Maintaining Power and Prestige: Even in clay form, the sheer scale and detail of the Terracotta Army reflect the emperor's desire to project power and authority into the afterlife.

The Decline of the Practice

While prevalent during the Qin dynasty, the practice of live burial gradually declined in later dynasties.

- Moral and Social Shifts: Buddhism and Confucianism, with their emphasis on compassion and human dignity, gained prominence, likely contributing to the practice's decline.

- Economic Considerations: Burying skilled workers and artisans represented a significant loss of human resources, which may have spurred alternative burial practices.

Q&A

Why was it considered inappropriate for Qin Shi Huang's concubines to remain alive?

The prevailing belief system dictated that the emperor needed companions and servants in the afterlife. Leaving his concubines alive was seen as denying him his rightful entourage, disrupting the cosmic order, and potentially leaving them in an "unclean" state as widows without a clear place in society.

Was the Terracotta Army a direct replacement for human sacrifice?

While not definitive, the presence of the Terracotta Army alongside evidence of human burial suggests a possible transition. The clay soldiers may have represented a growing discomfort with live burial while still fulfilling the need to provide for the emperor in the afterlife.

Why did the practice of live burial decline?

Several factors contributed to the decline, including the rise of Buddhism and Confucianism, which emphasized compassion and human life's value. Additionally, the economic burden of losing skilled workers likely played a role in shifting burial customs.